“The pelican, ready to wound itself to feed its young,…peers down at us from the pediments above doorways mutely saying, ‘How far will you go in giving of yourself?’” former headmaster John Ratté wrote in “Symbol, Tradition, and Myth in the Life of the School.” The myth goes that the vulning pelican pecks at its breast to feed its young.

His question is a daunting one. How far will you go in giving of yourself? How much will you sacrifice in service of something? Those are big questions for teenagers—and even adults—to answer. Nevertheless, his question, and the history in which it is rooted, are things I wish were made more overt at Loomis Chaffee. I’m incredibly happy with my experience at Loomis Chaffee. And while I find myself responding to Ratté’s question with an immediate, albeit wary, “I don’t know,” I feel as if I have come closer to an answer, especially during my last year here.

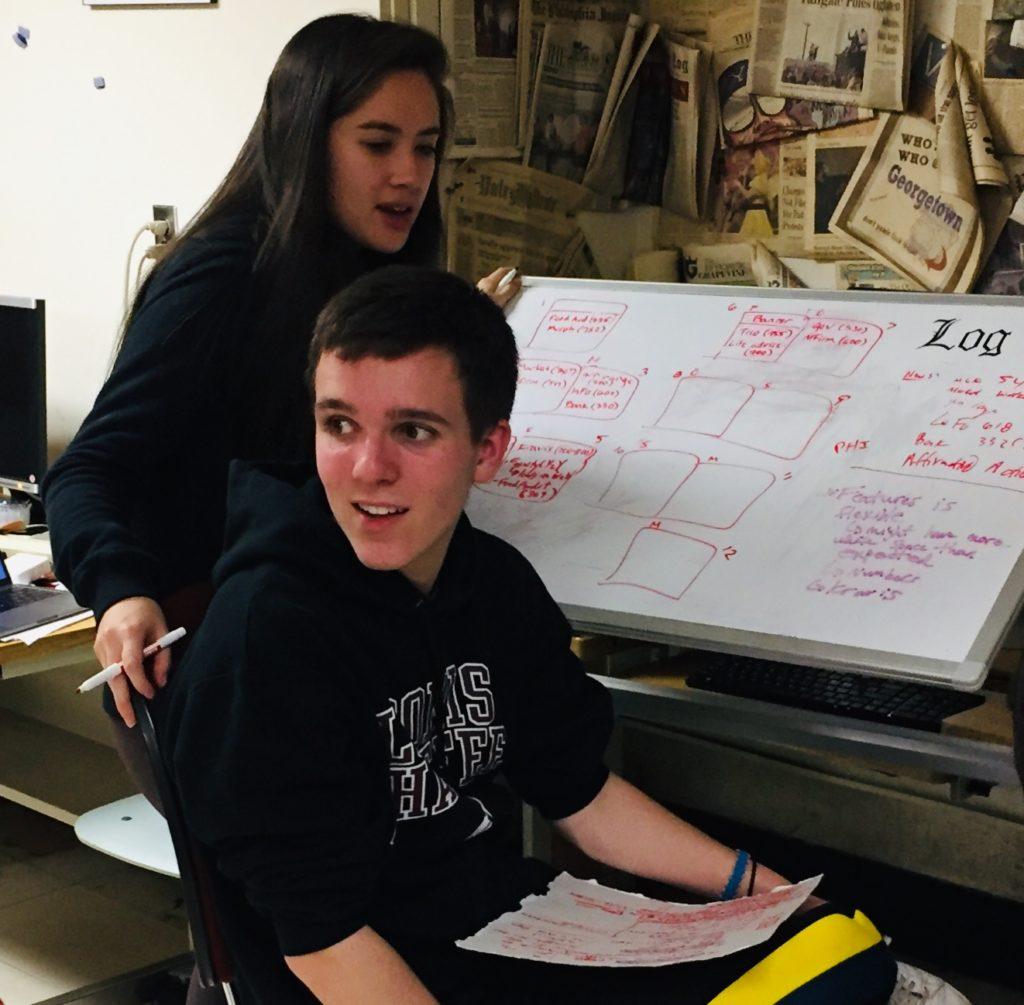

I’m grateful for the journey that brought me where I sit today—literally, in a blue couch in the library, and figuratively, more sure of myself than I have ever felt, and more empowered and inspired than I have ever felt. Getting here required time and, I realize now, a slight giving of myself—most prominently through leading The Log and designing the course Genocide: Media, Remembrance, and the International Community with Mr. Shure.

The history behind our giving pelican is complex yet rich in meaning. Coming from the Loomis family’s coat of arms, the pelican represents giving to young, maintaining the narrative of the Loomis family that founded a school in honor of their children, whom they all outlived. The pelican therefore “typifies a moral idea, course and purpose, life full of charity” and it is tied to our phrase ne cede malis (yield not to adversity), LC archivist Karen Parsons said. The pelican embodies “strength of moral purpose which is based on giving to others.”

The nature of our mascot, however, seems to have changed over time. I have looked at pelicans—on campus and off—and thought of the story of the school’s founders. However, I’ve never thought deeply about the pelican, and I haven’t gotten close to asking myself, or answering, how far I’ll go in giving of myself.

“I don’t know that we consciously see it [as John Ratté described the pelican], but we could, right, if we chose to attach that meaning to it,” Ms. Parsons commented.

“I think we’ve become much more playful with the pelican than maybe the founders ever imagined, which is fine. A mascot is meant to develop school spirit […] and then there could be that added layer of meaning about purpose,” she added.

Ratté expressed himself similarly: “Every institution has the possibility and the obligation to create its tradition and embody its symbols, its two- and three-dimensional icons, but principally its icons of word and deed in order to make more fully possible that modeling of interdependence and of self-discovery and self-making in society that is the school’s principal moral responsibility.”

In my experience, Loomis faculty have undoubtedly taught me the value of self-discovery and self-making (thank you, Mr. Shure, Ms. Hsieh, and Ms. Engelke). Self-discovery and self-making are some of the most valuable things I have learned while here, and I’m grateful for that. Nonetheless, I think the school as a whole could do a better job of reinforcing the importance of the school’s history and how that history informs how people can give themselves to something. Remembrance of that history is a form of tradition.